One of the foundational books of the “family education” genre, Harvard Girl Liu Yiting: A Character Training Record maintained a spot on China’s bestseller list for the first 16 months after its publication. It is essentially an in-depth guide for Chinese parents who want their children to study at Ivy League universities, which based on the book’s popularity and sales, represents a group of people in the millions. Not much has changed in the 17 years since the book took middle-class Chinese parents by storm in spring of 2000. For millions of students and parents alike, an American education is still the “dream” for which preparation in terms of both time and money starts early. Yet getting accepted at a respectable university is no longer enough. In order to remain competitive in their field, every student regardless of nationality, will need to fill in the space below the resume section heading titled Work Experience. Whether it’s navigating the technicalities surrounding a student visa or the ever-growing need for cultural intelligence, securing and succeeding in an American internship can be both daunting and complex.

Visas: A Quick How-To

The three most common visas for international students seeking an internship in the United States are J-1, M-1, and F-1 visas. In 2016, the United States issued 482,033 F-1/M-1 visas and 339,712 J-1 visas.

“The J-1 classification (exchange visitors) is authorized for those who intend to participate in an approved program for the purpose of teaching, instructing or lecturing, studying, observing, conducting research, consulting, demonstrating special skills, receiving training, or to receive graduate medical education or training.” The F-1 student visa is specifically meant for academic students and the M-1 is for “students in vocational or other nonacademic programs, other than language training.”

Both visas allow students to hold part-time on-campus jobs during the academic school year but only those students with F-1 status can work full-time on-campus during school breaks. Students on the J-1 visa who want to work full-time on-campus during school breaks must first get permission from their appointed Alternate Responsible Officer.

For F-1 students wanting to work off-campus full-time, for example in an internship capacity, they must either apply for Curricular Practical Training (CPT) or Optional Practical Training (OPT). CPT internships can be paid but must be directly related to the student’s degree. Typically students will receive some sort of academic credit for a CPT internship. In order to be eligible, students must have completed their first academic school year, must have a written offer of employment, must apply for authorization on their school visa, and receive an updated 1-20 form.

Optional Practical Training (OPT) internships differ from CPT internships in that they do not necessarily have to be a part of the student’s academic curriculum and can be done either while still enrolled (pre-completion OPT) or after the student graduates (post-completion OPT) or both (all periods of pre-completion OPT will be deducted from the available period of post-completion OPT). OPT is however, unavailable to F-1 students in English language training programs. Authorization for OPT internships does not require an offer of employment but requires an endorsement of the 1-20 form from the student’s designated school official, along with a notation in the Student and Exchange Visitor Information System (SEVIS), and the filing of a Form 1-765, Application for Employment Authorization Document (EAD) with the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services.

Certain students are eligible for an extension of the OPT period (up to 24 additional months for certain STEM majors). Applications can be submitted at any time prior to the expiration of a current OPT. If a student is offered full-time employment after their internship, they can petition to change their visa status from OPT to H1-B during their 60-day departure preparation periods.

What about entrepreneurs? F-1 students are eligible to start an entrepreneurial endeavor as long as it relates to their program of study and they are approved for OPT, either before or after graduation. Starting a business will rule out a student’s eligibility for the STEM OPT extension, since the applicant cannot be listed as their own employer.

Once an international student accepts an internship offer, the paperwork is fairly simple. First, the student must request a written offer from company headquarters on official letterhead that includes details such as the beginning and end date, the number of hours, pay, position title, supervisor, contact information, etc. The letter must then be brought to the university’s international student affairs office where they will process the necessary documents (usually between 3-5 days) and then present the student with a letter for the Social Security office. The processing of the letter typically takes a couple of hours in-person and then an additional two weeks until the student receives his or her official social security number. A small but important detail is that on-campus or CPT work must begin at least 15 but no more than 30 days from the application date.

Learning from Current International Students

Dandan Zhao, a visiting graduate student from Henan province in midland China found the internship recruiting process to be somewhat more difficult than she had anticipated. First of all, the environment is extremely competitive. Companies tend to already be somewhat hesitant about the possible language and cultural barriers associated with hiring a foreign student, not to mention the fear of investing in a potential hire that could be lost due to the H1-B lottery process. Not only are non U.S. citizen students competing against native-born Americans, but also scores of other internationals, working hard to go above and beyond to get the attention of recruiters. Dandan knew she had to work even “harder” than her American peers so she started to apply….to everything. “I began to interview with different companies 2-3 times a week. It was a lot but I think it made a difference in helping prepare me to better understand these companies and improve my interview skills.” This shotgun approach eventually landed Dandan a product management position with a global medical technology company for the summer.

Now at the half-way point of her internship, Dandan has found that the challenges for internationals don’t end with recruiting. While her coworkers are all very nice and helpful whenever she has questions, Dandan finds the nuances of American comedy to be the most tricky cultural hurdle in her daily routine. “I work on a very small, close team and I am the only intern. I’ve realized that there are some jokes that you just cannot understand, maybe about Star Wars or things you aren’t familiar with so you won’t get that sense of humor. Sometimes you just won’t be able to laugh at those jokes with your team and I find that very hard.” One way in which Dandan combats this potentially isolating situation is by being “really active”. “I try to be approachable and participate in all the activities. People are always asking me, ‘do you want to come to this activity?’ or ‘do you want to join this meeting?’ and I just automatically say yes.”

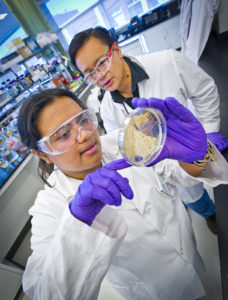

Prakash Singh moved to the U.S. from Bihar, India in the midst of the hot-button immigration issues of the 2016 election. He believes that this political climate had a direct effect on his internship recruiting efforts. “It was tricky, especially with the change of the new government and how the Trump administration is going to affect policies moving forward for those wanting to stay here and get a job. It was hard, harder than in years past.” Prakash learned quickly that he had a better chance of getting recruited to a company with an international presence, in the case that he got a job offer but not a work visa, he could be transferred to another location. Prakash eventually settled on Equinix, Inc., an American multinational interconnection company where he now works as a business analyst intern in San Francisco.

Whether company culture or American culture, he’s not sure, but Prakash noticed right away that the atmosphere was much different than his previous work as a software engineer analyst at Accenture, back home in India. “There don’t seem to be as many work deadlines – it seems a little more relaxed here. People have a lot of time to talk with their colleagues.” While it may not be what he’s used to, it’s clear Prakash has followed his own advice to, “Be receptive to a new culture and ideas. Don’t oppose the new things that you see. Be quick to learn and be confident to use what you learn and adapt to those changes. I have more and more interactions with people on my floor and around my cubicle, which is really good because I can create good relationships and learn a lot about the company.” Prakash is quick to add that it takes more than just passively accepting new practices from the people around you to succeed as an international student. “You have to make a good impression. Show them that you can do more than what they are expecting. If not, the company will say, ‘anybody can do that’. You really have to do something more, something out of the box, something they have not thought of or done before. Don’t be afraid to bring your unique experiences to the organization.”

When Lei Wang left hometown city of Yantai, China (population of over 6.5 million), she probably didn’t envision herself switching universities halfway through her graduate program or ending up working as the human resource talent acquisition intern at an outdoor gear company in Farmington, Utah (population of 22,159). When Lei talks about her experiences with recruiting, however, it is clear that flexibility and open-mindedness have been the keys to her success. Like most international students, Lei started by making a list of companies that are known to sponsor non-U.S. citizens for internships and jobs but unlike many of her peers, Lei chose to not limit herself. Companies like Dell, have repeatedly said that they do not offer sponsorships for human resources interns but Lei continued to network with the on-campus recruiters and student alumni and decided to go through with the application process anyway. “Make yourself necessary, and they’ll pick you,” she said, and they did just that. While she didn’t end up accepting that offer, Lei still learned a lot from the experience. “Be open to all opportunities! Some students give up because they see a company doesn’t offer sponsorship. A company may close the door but might open up a window for a sneak peak. If you want to stay in the U.S. you need to be very flexible in order to get a job. You don’t know which person could bring you the right resources or refer you to another company that does offer sponsorship.”

It is this same flexibility that has allowed Lei to explore several different options and discover that what she really enjoys doing is not necessarily what she came to America thinking she would pursue. Lately she has even considered returning to China to start her own business. “It’s quite common to not know what you really want when you first come to study in the U.S. Be flexible and don’t be afraid when there is something you want to change. Most students are still young and it doesn’t matter if they take some time to discover themselves.”

Roli Shukla is a self-declared introvert but hails from Delhi, one of the largest metropolitan areas in northern India. In terms of recruiting, Roli’s biggest struggle was answering the ambiguous question, “What makes you a good fit for this company?” “It’s not easy to know whether you fit with the company’s profile or not or to know how to demonstrate whether you’re a good fit – it’s a different culture – it was confusing… I don’t know anything about U.S. work culture and obviously the interviewer knows that I won’t know anything about it.” Roli figured that the best way she could prepare herself for these sorts of “culture evaluations” was to get as much information as she possibly could about the company. She read up on websites like Glassdoor and talked to everyone she could find who had interned there previously and also called current employees to ask more in-depth questions about the company values and overall work atmosphere.

This approach wasn’t meant to help Roli ‘trick’ the interviewer into thinking she was a good fit – it primarily helped Roli assess whether or not she herself would be happy at the company. According to Roli, being genuine with both the recruiters and yourself is essential. “Just be honest. During my interview, I think my honesty is what really helped me – I think it’s really valued. Just be open and frank and tell them if you have genuine questions. I think when you are honest, people are more willing and able to help you.”

In true introvert fashion, information gathering is one of Roli’s preferred tools. Not only has it helped her land a corporate strategy internship position with Fortune 500 company, Meritor Inc., it has also helped her adapt to the same cultural subtleties that she felt nervous discussing throughout the interview process.

Indian culture tends to have a reputation of hierarchy and a strong top-down structure throughout its society and organizations. In the corporate world Roli was used to, there is a large power distance between employees and their supervisors, that is workers are very much dependent on the boss for direction. To Roli, it seemed natural on her first day to ask what time she should be expected at work the next day. “Sometime between 7 – 9 am, he said. It was a shock to me that he gave me a range and not a particular time. But I realized that’s just how it must work here. For the first whole week I would ask for his permission to leave at the end of the day and I could see that he thought ‘Okay, why is she doing that?’ I realized that’s not something that happens a lot here so I started watching my coworkers and following them. That’s why observation is really great – it’s not specific to American culture but can help you adapt from one corporate culture to another.”

So while navigating the world of American internships may not always be simple, it is certainly not impossible. From the undecided Chinese explorer to the shy Indian observer, there is room for all personality types and backgrounds in the American workplace, so long as they are able to pick up on expectations, be versatile, and above all else, work hard.