U.S. Immigration News

Get updates on the latest in U.S. immigration news!

Federal Court Blocks Fee Increases

In July of 2020, USCIS announced they would be increasing green card, citizenship, and other fees.

Updated: Oct. 1, 2020

On Tuesday night (9/29/2020), a federal judge in California temporarily blocked U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) from increasing their fees.

In July, USCIS announced they would be increasing green card, citizenship, and other fees to “meet operational needs”. The fee increases were significant compared to previous fee increases implemented by USCIS, averaging 20 percent across all applicaiton types. According to the Immigrant Legal Resource Center, the changes included a new $50 fee for asylum applications, limited fee waivers and changed the criteria for fee waiver eligibility, and charged separate fees for Forms I-765 and I-131 when filed with Form I-485, which is more than a 60 percent increase.

In Tuesday’s opinion, Judge Jeffrey White of the United States District Court for the Northern District of California questioned the reasoning behind these fee increases. USCIS has not provided data to show why their financial situation has become so dire. The court agreed with the plaintiffs that the fee increases seem to be based on arbitrary and capricious arguments.

The court also questioned the legality of the fee increases as The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) does not have a Senate-confirmed secretary. The acting director of DHS, Chad F. Wolf, and previous acting director, Kevin McAleenan, were both appointed unlawfully under the Homeland Security Act and as such, they did not have the authority to issue the rule changes USCIS set forth as its final rule. The court concluded that the public has an interest in avoiding executive overreach and that appointments required informed consent of the Legislative branch.

In his ruling, Judge White also cited humanitarian protections for low-income and vulnerable immigrants. The fee increases would “expose those populations to further danger” he wrote.

The court’s injunction took effect immediately Tuesday night, so USCIS fees will not increase in the short term. However, the Trump administration will likely appeal the court’s decision.

COVID19 Immigration Updates

USCIS updates pertaining to COVID19

This article is updated as new information regarding the impact of COVID-19 on immigration is released.

October 1, 2021

Effective Oct. 1, 2021, applicants subject to the immigration medical examination must be fully vaccinated against COVID-19 before the civil surgeon can complete an immigration medical examination and sign Form I-693, Report of Medical Examination and Vaccination Record. This guidance applies to Form I-693 signed by civil surgeons on or after Oct. 1, 2021.

September 14, 2021

USCIS announces the COVID-19 vaccine will be required in order to complete the medical exam. Form I-693 to be updated shortly after.

August 2, 2020

A court issued an injunction against USCIS use of Form I-944, Declaration of Self-Sufficiency due to COVID-19 and its impact on the global economy. USCIS will not require submission of Form I-944 until further notice.

July 14, 2020

The policy which was put in place to required F-1 students taking classes online due to COVID to leave the United States was rescinded.

July 6, 2020

Student and Exchange Visitor Program (SEVP) announces that students taking online courses in the fall will not be allow to remain in the US during that time. This policy was later rescinded on July 14, 2020.

June 4, 2020

Certain USCIS field offices begin reopening. Appointments which were previously scheduled and cancelled will begin to be rescheduled.

May 1, 2020

USCIS issues an announcement that all responses to Requests for Evidence (RFE) and Notice of Intent to Deny (NOID) dated between March 1 and September 11, 2020 will be given an extension of 60 days from the date previously set to be due.

April 24, 2020

USCIS has announced that all routine in-person services have been suspended until at least June 4th, 2020, but has continued to fulfill roles that do require public interaction.

USCIS will provide emergency services for limited situations. To schedule an emergency appointment contact the USCIS Contact Center.

April 23, 2020

The executive order will not apply to:

- Temporary visas (student visas, H1-B visas, etc.)

- Green card applicants filing from within the United States (“adjustment of status“)

- Spouses or minor children of U.S. citizens

- Special Immigrant Visas or EB-5 (“immigrant investor”)

It will affect:

- Spouses of legal permanent residents (green card holders) filing from abroad (consular processing). Spouses and minor children of U.S. citizens filing abroad are exempt.

- Siblings, parents, and adult children of U.S. citizens filing from abroad.

April 3, 2020

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) released updates on their response to COVID-19. They stated that, “Detainee access to legal representatives remains a paramount requirement and should be accommodated to the maximum extent practicable. Legal visitation must continue unless determined to pose a risk to the safety and security of the facility”. In addition, where possible non-contact legal visitation should be offered. If it is determined that in-person visitation be necessary it will be permitted.

April 1, 2020

USCIS has announced that all routine in-person services have been temporarily suspended until at least May 3rd, 2020, but has continued to fulfill roles that do require public interaction. USCIS will provide emergency services for limited situations. To schedule an emergency appointment contact the USCIS Contact Center.

What this means for pending applications: No biometric appointments or interviews are currently being held. In cases where a biometrics is required and still incomplete that means that applications for work and travel authorization are not being processed at this time. Currently cases that require an interview will also remain pending until an interview can be scheduled.

March 30, 2020

USCIS announced that extension requests will reuse previously submitted biometrics in order to continue processing Employment Authorization Document (EAD) renewals.

March 27, 2020

USCIS issues an announcement that all responses to Requests for Evidence (RFE) and Notice of Intent to Deny (NOID) dated between March 1 and May 1, 2020 will be given an extension of 60 days from the date previously set to be due.

March 21, 2020

Policies between the United States and both Canada and Mexico go into place. These policies restrict non-essential travel across both borders. Travel will be permitted for matters such as work, school, and healthcare.

March 20, 2020

USCIS announces that they will accept all forms and documents with reproduced signatures dated March 21, 2020 and beyond.

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services today announced that, due to the ongoing COVID-19 National Emergency announced by President Trump on March 13, 2020, we will accept all benefit forms and documents with reproduced original signatures, including the Form I-129, Petition for Nonimmigrant Worker, for submissions dated March 21, 2020, and beyond. Keep copies of all original documents with signatures in case called upon to present them to USCIS as a later date.

Marcy 17, 2020

USCIS has announced that all routine in-person services have been temporarily suspended until at least April 1, 2020, but has continued to fulfill roles that do require public interaction. USCIS will provide emergency services for limited situations. To schedule an emergency appointment contact the USCIS Contact Center.

What this means for pending applications: No biometric appointments or interviews are currently being held. In cases where a biometrics is required and still incomplete that means that applications for work and travel authorization are not being processed at this time. Currently cases that require an interview will also remain pending until an interview can be scheduled.

March 13, 2020

USCIS announced that seeking treatment for COVID-19 will not negatively impact immigrants under public charge.

Travel restrictions to the US are put into place from two dozen European countries. This restriction does not apply to US citizens and permanent residents, their spouses, their unmarried siblings under 21, and their children.

* March 14th Ireland and England are added to list of restricted travel.

Visitor Visa 30/60 Day Rule Becomes 90 Day Rule: What Does that Mean?

Understanding the policy change to the 30/60 day rule.

Last Updated: January 15, 2020.

Recently, the Trump administration changed a policy that places foreign nationals under advanced scrutiny.

If a foreign national takes any actions within 90 days of entering the country that are not compliant with his/her visa status, it will likely be presumed that they willfully made a misrepresentation about their motives for entering the country.

This new rule is called the 90-day rule and it replaces the 30/60-day rule. It marks a small yet significant change in immigration policy.

The change became official on September 1, 2017, when the Department of State updated the Foreign Affairs Manual (FAM). It is important to note the rule is not a statute, nor is it an official regulation; it is better seen as an advisory principle created to help consular officers if a subsequent violation of visa status qualifies as a “ willful misrepresentation” in the initial visa application.

The new rule is found in 9 FAM 302.9-4. To better understand the significance of this rule and the recent change, let’s take this rule section-by-section.

9 FAM 302.9: Discusses some of the many reasons aliens can be inadmissible for various reasons

So the FAM is a extensive handbook Department of State officials use to, among other things, make immigration decisions. Chapter 9 of the FAM deals with visas. Section 302 outlines all the myriad ways an alien can become ineligible for a visa. Section 302.9 outlines the reasons aliens can be ineligible for entry under INA 212(a)(6).

The INA is the Immigration and Nationality Act. It is codified in §1182 of the United States Code, which is basically a very large book containing all the laws of the U.S. INA 212(a)(6)(C) says:

Any alien who, by fraud or willfully misrepresenting a material fact, seeks to procure (or has sought to procure or has procured) a visa, other documentation, or admission into the United States or other benefit provided under this chapter is inadmissible.

In layman’s terms, this means anyone who has lied — or willfully misrepresented — about something important — a material fact — in a visa application may not receive a visa.

To mere people like ourselves, it may seem like common sense is all that is needed to determine whether something is a “misrepresentation.” However, when money and people's lives are on the line, “common sense” doesn’t cut it. That’s why the State Department wrote a whole section on how to determine whether an action is a “misrepresentation.” That section is 9 FAM 302.9–4.

9 FAM 302.9-4(B)(1): Provides four criteria for finding a misrepresentation

9 FAM 302.9-4 discusses reasons for an alien’s inadmissibility due to a misrepresentation. 9 FAM 302.9-4(B)(1) outlines four criteria required for finding misrepresentation. For an alien to be inadmissible because of a misrepresentation it must be determined that:

- There has been a misrepresentation made by the applicant;

- The misrepresentation was willfully made;

- The fact misrepresented is material; and

- The alien by using fraud or misrepresentation seeks to procure, has sought to procure, or has procured a visa, other documentation, admission into the United States, or other benefit provided under the INA.

In plain English, the misrepresentation must be made by the person applying for the visa, it must have been done willfully, it must have been about something important, and it must have been for purpose of obtaining a visa or other benefit.

Let’s see what each of these criteria entail.

(B)(3): Defining misrepresentation

Section (B)(3) defines “misrepresentation.” First, it provides a basic definition: a misrepresentation is an assertion or manifestation not in accordance with the facts. Misrepresentation requires an affirmative act taken by the alien. A misrepresentation can be made in various ways, including in an oral interview or in written applications, or by submitting evidence containing false information.

Let’s look at this more closely.

a misrepresentation is an assertion or manifestation not in accordance with the facts. This provides for a broader definition than a lie — a lie being a false statement made with the intention to deceive — this encompasses a statement that was purposefully made, that is untrue, but was not made with the intent to deceive. As is discussed below, a misrepresentation must be made willfully, which means its lower limit is set somewhere above a mere mistake. Additionally, (B)(2) defines the upper limits of misrepresentation: it is something less than fraud. Fraud must be shown by evidence of the intent to deceive and an officer must actually believe the lie.

Misrepresentation requires an affirmative act taken by the alien.This statement differentiates between a statement and a silence. Here, silence, or failure to volunteer information, does not by itself amount to a misrepresentation.

A misrepresentation can be made in various ways, including in an oral interview or in written applications, or by submitting evidence containing false information.This statement suggests a few additional points. The misrepresentation must be made by the alien — or the aliens agent or attorney so long as the alien was aware of the action. The misrepresentation must be made before a U.S. Official, which means it could be made orally or in written form most likely before a consular officer or a Department of Homeland Security officer. The misrepresentation must be made on the alien’s own application, not in regards to someone else’s application.

It should be noted that a “timely retraction” could remedy the misrepresentation. Timeliness depends on the circumstances of the particular case; a retraction should be made at the first opportunity to be safe.

(B)(3)(g): States that activities that are inconsistent with an alien’s visa status are a red flag.

(B)(3)(g) dives into a tricky topic, one that is at the center of the 90-day rule: activities inconsistent with visa status. It states: In determining whether a misrepresentation has been made, some of the most difficult questions arise from cases involving aliens in the United States who conduct themselves in a manner inconsistent with representations they made to consular officers concerning their intentions at the time of visa application or to DHS when applying for admission or for an immigration benefit. Such cases occur most frequently with respect to aliens who, after having obtained visas as nonimmigrants and been admitted to the United States, either: Apply for adjustment of status to lawful permanent resident; or fail to maintain their nonimmigrant status (for example, by engaging in unauthorized study or employment).

This passage states that immigration officers are sometimes faced with the difficult task of interpreting an alien’s inconsistent behavior. Oftentimes this occurs when an immigrant applies for lawful permanent residence or fails to maintain her nonimmigrant status.

Since it’s difficult for immigration officers to know what to do in this case, the Administration created the 90-day rule.

(B)(3)(g)(2) & (3): Shows when the 90-day rule should be used

The 90-day rule is mostly about a legal concept called presumption. A presumption is an idea that is taken to be true, and often used as the basis for other ideas, although it is not known for certain. It’s similar to an assumption but not quite as strong. It is most easily exemplified in the phrase “innocent until proven guilty.” In murder trials in the U.S., a suspect is presumed innocent until proven guilty. That means it is the prosecution’s job to prove the defendant is guilty, not the defendant’s job to prove that she is innocent.

It is the same case here: an alien that behaves inconsistently with the representations made in her visa application is presumed to have made the representations not willfully — unless those inconsistent actions are made within 90 days of her entry into the U.S. This is because if inconsistent action is taken so quickly after arriving in the U.S. it is arguably likely the alien lied about her intentions for coming in the first place.

Previously, under the 30/60 day rule, if an alien made inconsistent actions within 30 days of entry, the misrepresentations made in her application were presumed to be willful. Now, under the 90-day rule, that time period has been extended from 30 days to 90 days. As the names imply, that is the primary substantial change made to the rule.

The new rule states:However, if an alien violates or engages in conduct inconsistent with his or her nonimmigrant status within 90 days of entry . . . you may presume that the applicant's representations about engaging in only status-compliant activity were willful misrepresentations of his or her intention in seeking a visa or entry.

The rule also requires the immigration officer to request an advisory opinion on the case.

So, if inconsistent conduct is made, the presumption shifts against the alien, and the alien now has the responsibility to prove she did not make the misrepresentations willfully.

The section continues to list some specific conduct that would be inconsistent or in violation of an alien’s nonimmigrant status:

- Engaging in unauthorized employment;

- Enrolling in a course of academic study, if such study is not authorized for that nonimmigrant classification (e.g. B status);

- A nonimmigrant in B or F status, or any other status prohibiting immigrant intent, marrying a United States citizen or lawful permanent resident and taking up residence in the United States; or

- Undertaking any other activity for which a change of status or an adjustment of status would be required, without the benefit of such a change or adjustment.

So, becoming employed, enrolling in school, marrying a citizen, or doing other activities that require an adjustment of status could put an alien at risk of coming under the 90-day rule.

If inconsistent conduct only occurs after 90 days have passed, then the presumption does not shift against the alien.

(B)(4) & (5): Defines “willfully” and “material fact”

For an alien to be inadmissible under INA §212(a)(6), which the 90-day rule applies, she must make a misrepresentation willfully. Willful is a definable legal concept and the FAM states:

In order to find the element of willfulness, it must be determined that the alien was fully aware of the nature of the information sought and knowingly, intentionally, and deliberately made an untrue statement.

In other words, the alien must knowingly make the untrue statement, which is notably different from making an untrue statement with intention to deceive.

The misrepresentation must also be material. Materiality, like willfulness, is another legal concept. In this case a misrepresentation is material if:

- The alien would have been inadmissible if the true facts were revealed, or

- The misrepresentation cut off a line of questioning that would have lead to the determination that the alien was inadmissible.

So, in other words, most topics an applicant might have an interest in hiding are material.

Key Takeaways

For aliens submitting visa applications: Do not lie about your motives for application. For visiting aliens interested in changing your status: Do so very carefully, probably only after 90 days have passed since your entry.

Trump & the 2017 Travel Ban: Who does it affect?

Trump's 2017 travel ban restricts visas for 8 countries with few exceptions and added vetting.

Last Updated: January 15, 2020.

The Trump administration is carrying out a change to immigration policy, commonly known as the Travel Ban. This update aims to prohibit entry of nonimmigrants and immigrants who are nationals from 8 countries; Chad, Iran, Libya, North Korea, Somalia, Syria, Venezuela, Yemen. Each country has its own set of specific restrictions. Instead of a 90-day vetting period like the first version, this ban is basically indefinite. To break it down, the new update is being carried out in two phases. September 24, 2017 marked the beginning of phase 1 and phase 2 will start on October 18. Trump administration announced that the update does not apply to refugees, but they will have a separate policy regarding refugees from these 8 countries forthcoming. We'll pinpoint the takeaways from this ban for those who may be affected in any way. Before we delve in, it helps to understand why these new regulations exist.

This new order, compared to its predecessors, takes on an even longer name: "Enhancing Vetting Capabilities and Processes for Detecting Attempted Entry into the United States by Terrorists or other Public-Safety Threats".

"Making America Safe is my number one priority. We will not admit those into our country we cannot safely vet" - Donald J. Trump, Sept 24, 2017

Essentially, this newer order follows up or implements the next step to version 2 from back in March. Previously, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) conducted a worldwide review using a set of criteria to evaluate each foreign countries' information-sharing practice, policies, as well as each governments' stability and capabilities. At the end of this review, the Trump administration blacklisted 8 countries whose information sharing practices were deemed "inadequate" or otherwise the president has "special concerns" toward. The travel ban has significant ramification for United States' diplomatic relationship on the international level, but let's take a look at what it means to the individuals who are these countries nationals.

According to this Travel Ban update, "U.S. embassies and consulates will deny visas to most cases from the 8 blacklisted countries, with few exceptions that will require extensive screening and vetting process.

- Chad: No immigrants or diversity visas will be issued; No nonimmigrants visas B-1, B-2, and B-1/B-2 will be issued; as of September 24, "bona fide relationship" exception is no longer acceptable. **Quick refresher, "bona fide relationship" extends to those who have close family members who are U.S. citizens such as parents, parents-in-law, spouses, fiancé or fiancee, child, adult son or daughter, son or daughter-in-law, sibling, brother or sister-in-law, grandparent, grandchild, aunt, uncle, niece, nephew, first-cousin, and for all listed relationships, half or step relationships is included.

- Iran: No immigrants or diversity visas will be issued; no nonimmigrant visas except F, M, and J student visas; during phase 1 (from September 24, 2017 to October 17, 2017), the "bona fide relationship" exception still applies and ends when phase 2 (October 18, 2017) starts.

- Libya: No immigrants or diversity visas will be issued; No nonimmigrant visas B-1, B-2, and B-1/B-2 will be issued; During phase 1 the "bona fide relationship" exception is still accepted, but it ends when phase 2 starts.

- North Korea: No immigrant, nonimmigrant, or diversity visas will be issued. No "bona fide relationship" exception accepted.

- Somalia: No immigrant or diversity visas; nonimmigrant visas face no restriction. During phase 1 the "bona fide relationship" exception is still accepted, but ends when phase 2 starts.

- Venezuela: No immigrant visa restrictions; No nonimmigrant visas B-1, B-2, and B-1/B-2 will be issued for officials and their immediate family members from the following government agencies: Ministry of Interior, Justice, and Peace; the Administrative Service of Identification, Migration, and Immigration; the Corps of Scientific Investigations, Judicial and Criminal; the Bolivarian Intelligence Service; and the People's Power Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

- Yemen: No immigrants or diversity visas will be issued; No nonimmigrant visas B-1, B-2, and B-1/B-2 will be issued. During phase 1 the "bona fide relationship" exception is still accepted, but ends when phase 2 starts.

From these countries, any individual who may be able to obtain a visa will still have to face extensive screening and vetting process upon entering the United States.

How will these new restrictions affect issued visas or currently processing visas?

- If you've already obtained a visa, then your visa is safely yours. The new order specified that no visas issued before its effective date will be revoked. Therefore, if you've obtained a valid visa but have yet to enter the United States, then the restrictions do not apply to you.

- If your visa expires after the effective date, then you will not be able to renew your visa if your case is under the restrictions.

- If your visa is currently in the works, then here are the specifics:

- First, the Trump administration has stated that it won't cancel previously scheduled visa application appointments.

- Second, it's up to the consular officer to determine if the course of interview whether an applicant's case is exempt from the new restrictions, be eligible for a waiver, or falls under the 2 phases of restrictions.

- Third, The National Visa Center (NVC) continues to work on cases that are in process, so applicants should still pay their fee, complete all necessary forms, and submit the paperwork to the NVC.

- For those who are currently applying for the K (fiancé) visa, the NVC is expediting all I-129F petitions. Once the petition and case files are processed, the embassy or consulate will contact you to schedule an interview.

- If you recently had an interview at a U.S. Embassy or Consulate, but your case is still being considered:

- Make sure you've sent in all missing documents and completed any of the administrative processing. The embassy or consulate where you were interviewed will contact you. It's still up to the consular officer to determine the status of your case.

- Following the two phases of implementation, all bona fide cases both familial relationship and relationship with an entity will only be available during the first phase. After the second phase starts, the bona fide relationship exception will be no longer available.

Sponsoring family members for an immigrant visa

While the Trump administration's new travel ban is underway, the Supreme Court was originally scheduled to hear arguments on President Trump’s travel ban on October 10, 2017 but cancelled it immediately.

Trends in Global Immigration

Understanding trends in global immigration.

Last Updated January 15, 2020.

Every year, millions of people leave their home countries and move to a new one. They do so for numerous reasons; perhaps they're seeking adventure, economic opportunity or a better quality of life for themselves and their children. Others seek refuge from political turmoil in their homeland.

No matter the reason, we can examine their numbers to discern trends in global migration. What can be inferred about immigration to the U.S. and abroad — and what can be expected as we get move into the last part of 2017 and beyond? That's what this article aims to answer. Today we're looking at the current trends in global migration.

Relevant terms:

Before we look at the these trends, let's define some common terms

Migration: The process of moving across a border with the goal of taking up permanent or semi-permanent residence.

Migrant flow: The number of people migrating within a specific time frame.

Migrant stock: The total number of people residing in the country that is not the one in which they were born. This is also known as a country's "foreign-born population."

International migration: The act of moving from one country to another.

International migrant: Someone who has been living for a year or more in a country other than the one they were born in.

International Migrants by the Numbers

This chart from the United Nations Population Division breaks down the total number of people living in a country in 2015 other than the one in which they were born. The 25 countries that are home to the largest groups of migrant stock are:

- United States

- Germany

- Russian Federation

- Saudi Arabia

- United Kingdom

- United Arab Emirates

- Canada

- France

- Australia

- Spain

- Italy

- India

- Ukraine

- Thailand

- Pakistan

- Kazakhstan

- South Africa

- Jordan

- Turkey

- Kuwait

- Hong Kong SAR, China

- Iran, Islamic Rep

- Singapore

- Malaysia

- Switzerland

U.S. - Global Leader in Immigration by Absolute Number

With approximately 46.6 million migrants, more people migrate to the United States than any other nation. However, that's just absolute numbers; while the U.S. has the most immigrants in the world, that makes up only 14 percent of its population. This "immigrant share" is much lower than the percentages seen in many Middle East countries including the United Arab Emirates, Qatar and Kuwait, where approximately three out of four people are international migrants.

In addition, 28 percent of Australia's population is foreign born and 22 percent of Canada's is foreign born. So while the U.S. tops the list in absolute numbers, these countries have a greater share of their population that was born in a different country.

Other Countries Leading Global Immigration

In absolute numbers, Germany was the second most popular destination country for international migrants, followed by the Russian Federation.

As a percentage of the country’s population, the numbers are highest in the following Middle East countries:

- International migrants make up a whopping 88.4 percent of the total population in the United Arab Emirates

- International migrants make up 75.7 percent of the total population in Qatar

- International migrants make up 73.6 percent of the total population in Kuwait

Is migrant flow increasing?

In terms of absolute numbers, yes — the numbers continue to climb. But as a share of the global population, the numbers budge only slightly. Let's take a look:

- The absolute numbers of international migrants has grown from approximately 79 million in 1960 to almost 250 million in 2015, a 200 percent increase. So by sheer numbers, there are far more international migrants today.

- But by percentage of the world’s population, international migrant numbers today are only slightly higher than 1960 numbers. The world population in 1960 was about 3 billion; in 2015, that number was 7.3 billion. When you calculate these ratios, you find that in 1960, 2.6 percent of the global population did not live in their birth countries; in 2015, that figure rose only slightly, to 3.3 percent.

Trends of note

1. The Mexico-U.S. migration path: Net flows are reversing

One of the world's biggest pathways for international migration has always been from Mexico to the United States. As of 2015, about 12 million Mexico-born people were living in the U.S. But as Pew Research notes, these numbers are reversing; more Mexican immigrants have returned to Mexico from the U.S. than have migrated here since 2009.

2. India to the Middle East becomes a major pathway

Another notable migration path is from India to the UAE. As of 2015, almost 3.5 million India-born people lived in the UAE. This number indicates a major trend still for years to come: The number of Indians living in the Middle East has grown from 2 million in 1990 to more than 8 million in 2015.

3. Nearly 1 in 5 migrants live in the world's top 20 largest cities

And the percentages of international migrants living in these cities is notably high. For example: 33 percent of the total population of Sydney, Auckland, Singapore and London is international migrants; and 25 percent of the total population of Amsterdam, Frankfurt and Paris is international migrants.

Global Refugees & Asylum-Seekers

Trends to note here include:

- The number of people who were forcibly displaced in 2015 was the highest it's been since World War II. Worldwide, an astounding 15.1 million people were considered refugees. This huge number is largely attributed to the conflict in Syria, where about 8.6 million people were displaced just in 2015.

- Germany was the single largest recipient of worldwide refugees in 2015 — nearly 442,000 asylum-seekers moved to that country that year. If you factor out this large inflow of refugees, Germany still overwhelmingly holds the number 2 spot for countries having a foreign-born population. More than 12 million people came to Germany in 2015.

- Worldwide, the number of people seeking asylum grew dramatically from 2014 to 2015, with 558,000 applications pending at the end of 2014 to 3.2 million pending asylum applications globally by the end of 2015.

- The European Union received 1.2 million asylum applications in 2015, more than double the asylum applications filed in 2014. This is attributed to record numbers of asylum seekers from Syria, Afghanistan and Iraq.

- A third of the people who filed for asylum in the EU were minors; tragically, one in 4 of this group was judged to be unaccompanied by an adult.

- The majority of asylum seekers look to neighboring countries to host them, however, even if that host country is a developing country itself. For example, most of the Syrian refugee population in 2015 lived in Turkey (2.2 million), Lebanon (1.2 million) and Jordan (almost 630,000).

- The world is facing a new global refugee crisis in Southeast Asia. As of October 2017, 800,000 forcibly displaced Rohingya people from Myanmar have poured into Bangladesh. They are escaping what UN human rights officials are calling "a textbook example of ethnic cleansing."

American & European views on their migrant populations

What do Americans think of immigrants?

According to a 2016 Pew study:

- 63 percent of U.S. adults felt that immigrants strengthen the country through their hard work and talents

- 27 percent feel immigrants are a burden on the country by taking jobs, housing and health care

This is a reversal of a similar study conducted in the 1990s, when 63 percent of respondents said immigrants were a burden on the U.S. and only 31 percent believed immigrants helped the country.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, certain groups were found to hold more favorable views of immigrants than others. For example, Democrats were more likely than Republicans to say immigrants benefit the U.S., and younger people held more positive views than older people.

What do Europeans think of immigrants?

The influx of refugees in Europe has deeply divided people in the region. In a 2016 study of 10 European countries, it was found that:

- Half or more of the adults in eight out of the 10 nations fear that refugees will boost the chances of terrorism in their countries

- Half or more of the adults in five of the 10 countries believe refugees will harm their economies by taking jobs and social benefits

- Perhaps most shockingly is this finding: In none of the 10 countries surveyed did a majority of the respondents say that increasing ethnic diversity would be a positive thing for their nation.

What do Australians think of immigrants?

Australia is another nation where emotions run deep on the matter of immigration. Earlier this year the prime minister announced vast immigration and naturalization reform, seemingly in response to a less welcoming attitude among his countrymen. Findings of a 2016 study from the Scanlon Foundation support this theory. Among its key takeaways:

- As many as six million Australians feel negatively about Muslims

- 20 percent of non-White Australians born abroad reported discrimination in 2016; more than a third of these felt they were being denied jobs or promotion because of their ethnicity

- The news isn't all bad: 66 percent of respondents said that receiving migrants from many nations makes Australia better

Will the United States continue to dominate global migration?

If one only looked at the historical data for an indication of this, the answer would be a resounding "yes." But immigration in a Trump-era America is uncertain at best. Members of Congress have put forth legislation that could change the categories of immigration and drastically reduce the number of visas granted across the board. Others are taking aim at certain family based categories. Confusion and uncertainty reign here; only time will tell.

Additional statistics and analysis provided by Pew Research Center and the Global Migration Data Analysis Centre, International Organization for Migration.

Trump's New Immigration Bill: What's The Point?

Understanding the basics of Trump's new immigration bill.

Last Updated: January 15, 2020

On August 3, 2017 Trump announced his support of S. 1720, a bill introduced by Senator Tom Cotton of Arkansas and co-sponsored by Senator David Perdue of Georgia, two Republicans. Trump said: “This legislation demonstrates our compassion for struggling American families who deserve an immigration system that puts their needs first and puts America first."He called it the “RAISE Act;” short for “Reforming American Immigration for a Strong Economy Act.”The RAISE Act was initially introduced to the Senate back in February and was referred to the Senate Judiciary Committee. It was then revised and reintroduced in August.Trump's adviser Stephen Miller and former adviser Steve Bannon promoted and helped shape the bill.

Many have dismissed this bill because it has not attracted any additional co-sponsors, and Republican leaders in Congress have no plans to vote on it in 2017. However, the bill remains relevant as it gives insight into the thoughts of the President and other leading figures on their ideal immigration system. Additionally, although this bill may not pass, it may influence another bill in the future.Section-by-section, the bill seeks to:

- Section 2: Eliminate the visa diversity lottery program

- Section 3: Enforce the 50,000 annual refugee cap. 84,995 refugees entered the US in 2016.

- Section 4: Narrow the meaning of “immediate relatives”.

- Section 5: Replace the employment-based immigration system with a points-based immigration system

- Section 6: Add one prerequisite for naturalization

These sections altogether would result in around a 30 percent reduction to green cards issued. Let’s take a look at each section in turn.(For more numbers on green cards, take a look at this frequently cited report.

SECTION 1: SHORT TITLE

It states the short title.This Act may be cited as the “Reforming American Immigration for a Strong Economy Act” or the “RAISE Act”.

SECTION 2: ELIMINATES THE DIVERSITY IMMIGRANT VISA PROGRAM

After Section 1, things start to get hairy quick. Section 2 eliminates the diversity visa program.The Diversity Immigrant Visa program, also known as the green card lottery, allows would-be immigrants to receive a United States Permanent Resident Card, or green cards, through a lottery system. This system was established in The Immigration Act of 1990.The lottery provides 50,000 green cards each year and aims to diversify the immigrant population in the United States. To do this it selects applicants from countries with low rates of immigration in the five years prior.Eligibility is determined by the applicant’s birth country, not country of residence. Section 2 eliminates all of that.

“(a) In General.—Section 203 of the Immigration and Nationality Act (8 U.S.C. 1153) is amended by striking subsection (c).”

SECTION 3: REMOVES EXCEPTIONS FOR THE ANNUAL REFUGEE CAP OF 50,000

Section 3 establishes a refugee cap of 50,000 that kind of, debatably, already existed. At the very least, it removes exceptions to the 50,000 rule.This section makes major changes to 8 U.S.C. 1157. 1157 says: the number of refugees who may be admitted may not exceed fifty thousand . . . unless the President determines . . . that admission of a specific number of refugees in excess of such number is justified by humanitarian concerns or is otherwise in the national interest.But that clause apparently only applied to a few years in the early eighties. Ever since then Presidents have been welcoming however many refugees they want.(Take a look here for refugee numbers.)Also, President Trump has tried to cap the refugee intake at 50,000 in various ways already. So again, at the very least, this bill eliminates the options for the President to raise the cap for “grave humanitarian concerns” or the “national interest.” The new code would read:

“(1) IN GENERAL.—The number of refugees who may be admitted under this section in any fiscal year may not exceed 50,000."

Also, an interesting change: special discretionary decision-making power is transferred from the Attorney General to the Secretary of Homeland Security. So the Secretary of Homeland Security would be able to admit any refugee who is not firmly resettled in any foreign country, is determined to be of special humanitarian concern to the United States, and is otherwise admissible as an immigrant.

SECTION 4: LIMITS THE REACH OF FAMILY SPONSORED VISAS

This section primarily narrows the meaning of “immediate relative.” It effectively removes family-visa pathways for siblings and adult children of U.S. citizens and permanent residents to apply for permanent residency status in the U.S. It limits the family path to spouses and minor children.It redefines “immediate relative” as spouse and children under 18 years old. Whereas before it included children up 21, parents, and siblings.

“Family-sponsored immigrants described in this subsection are qualified immigrants who are the spouse or a child of an alien lawfully admitted for permanent residence.”

It allows for 88,000 immigrants minus the number of aliens paroled that did not depart and did not acquire the status of an alien lawfully admitted. It also deals with some rather complicated things like how many of these visas are subject to country limitation and when the visa of a dependent parent can be extended.

SECTION 5: REPLACES THE EMPLOYMENT-BASED IMMIGRATION SYSTEM WITH A POINTS BASED IMMIGRATION SYSTEM

Section 5 establishes a point-system which would replace the employment-based system with the points based system. This is one of the more innovative or creative sections; the system is surprisingly simple. Notably, the caliber of immigrants accepted under the current employment-based system is already remarkably high. So, If the points-based system were implemented then a sufficiently large number of applicants would accrue enough points to maintain a large applicant pool — a large enough pool to keep the number of employment sponsored green cards the same.Raise keeps the current level of employment visas which is 140,000.

“(1) IN GENERAL.—The worldwide level of points-based immigrant visas issued during any fiscal year may not exceed 140,000."

The points system invites any qualifying applicant to apply for submission into the eligible applicant pool. Applicants apply online and pay a $160 fee. An applicant is eligible if they accrue over 30 points. The applicants with the highest point counts are then siphoned off the top every six months until 140,000 people are admitted.Selected applicants are invited to submit another application which would include valid documentation, an attestation from the prospective employer, the annual salary being offered, a declaration that the job position is new or vacant, health insurance records, and a fee of $345.If the applicant is accepted, spouses, minor children, and dependent adult children can also be issued a visa.In regards to the points, the goal is to accrue 30 points. Points are allotted by status in each category.

Would You Qualify for Legal Immigration to the U.S.?

Answer the following questions to find out:

Age:

- 0–17: Ineligible

- 18–21: 6 points

- 22–25: 8 points

- 26–30: 10 points

- 31–35: 8 points

- 36–40: 6 points

- 41–45: 4 points

- 46–50: 2 points

- 51 and older: No points

Education:

Points are awarded only for the highest degree obtained.

- US or foreign high school: 1 point

- Foreign bachelor’s degree: 5 points

- US bachelor’s degree: 6 points

- Foreign master’s degree in STEM: 7 points

- US master’s degree in STEM: 8 points

- Foreign professional degree (including MBA, JD, or MD) or doctorate in Stem: 10 points

- US Professional degree or doctorate in stem: 13 points

English Language Proficiency:

Points are awarded for decile placement in IETSL or TOEFL.

- 1st–5th deciles: 0 points

- 6th–7th deciles: 6 points

- 8th decile: 10 points

- 9th decile: 11 points

- 10th decile: 12 points

Extraordinary achievements

- Nobel Laureate or has received comparable recognition in a field of scientific or social scientific study: 25 points

- Earned an individual Olympic medal or placed first in an international sporting event within the last 8 years: 15 points

- None 0 points

Job Offer

Points are awarded for job offers with high monetary compensation.

- Annual salary 150%–200% of median household income of state: 5 points

- Annual salary 200%–300% of median household income of state: 8 points

- Annual salary 300% and above of median household income of state: 13 points

- No Job Offer 0 points

Investments

- Applicant agrees to invest $1,350,000 in a new commercial enterprise in the US: 6 points

- Applicant agrees to invest $1,800,000 in a new commercial enterprise in the US: 12 points

- No Investment 0 points

Family preference

- The applicant previously qualified for the once valid family preference visa category: 2 points

Requirement

- An applicant is ineligible if he doesn’t have a degree higher than a bachelor’s degree and he is not in the 6th decile or higher for English proficiency.

Spousal consideration

- If an applicant’s spouse would accrue higher points, then no change is made to the applicant’s points. However, if the spouse would accrue lower points, then 70% of the applicant’s points would be added to 30% of the spouse’s points, and this new number would be considered

Minimum Score: 30

You must be at least 18 years old and have at least 30 points to be eligible to apply for immigration, according to proposed legislation.

SECTION 6: CHANGES THE PREREQUISITE FOR NATURALIZATION

Section 6 mostly does some housekeeping to an already standing section of US code. However, at the end, it adds a term that disqualifies from naturalization people who have outstanding debts owed to the federal government.And that’s the RAISE Act explained section-by-section. We’ll see what bill comes next for immigration.

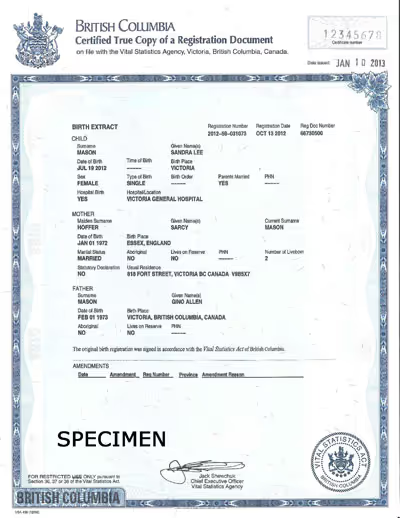

Canadian Birth Certificates & Green Cards: What You Need

Understanding Canadian birth certificates needed for green card applications.

Last updated: January 15, 2020

If you are from Canada and you are trying to get your green card you will need a specific copy of your birth certificate. You may be asking, "Which birth certificate will the USCIS accept for Canadian citizens?" or "Where to I get a copy of my Canadian birth certificate for a green card?" The following is a guide that will help you know which type of birth certificate is preferred by the USCIS and will be accepted with a green card, legal permanent residency application. Every year tens of thousands of Canadian-born immigrants go through the immigration process in the United States. At SimpleCitizen, we are proud of the fact that a large percentage of our customers hail from the Maple Leaf. Our friends from Canada enjoy special rules when obtaining visas, green cards and citizenship. Although some of the special rules make it easier for Canadian citizens to come to the United States they can cause some confusion as Canadians try to submit green card or citizenship applications. An essential and required piece of the green card application is a copy of the applicant’s birth certificate. This requirement is the source of a lot of confusion for Canadians trying to prepare an Adjustment of Status application for Legal Permanent Residency. Birth certificates in Canada are issued by the individual Province or Territory where the birth took place. There are basically two types of birth certificates that can be issued:

The Short Form or Small

This certificate is printed on a small card. It is usually the size of a standard driver’s license and small enough to fit in a wallet (9.5 x 6.4 cm / 2.5 x 3.75 in). These certificates are not accepted by the USCIS or the DHS because they do not have required information such as the names of parents.

The Long Form, Large or Full-size

This certificate is a printed copy from the records of the province. It is usually on “currency-style paper stock” with intaglio border (21.6 x 17.8 cm / 7 x 8.25 in). These certificates are accepted by the USCIS and the DHS.There are specific types of birth certificates and each province has their own name for the certificate that is accepted by the USCIS and their own process for obtaining a copy. The following is a province-by-province guide for getting the right birth certificate attached to your green card application for the USCIS.

Alberta

If you were born in Alberta you need to attach a copy of your "large sized" certificate. If you don’t have a copy you can work with the Alberta Vital Statistics using a private Alberta Registry Agent. If you need information on official Registry Agents they are available online.

British Columbia

If you were born in British Columbia you need to attach a copy of your "large" certificate. If you don’t have a copy you can request one from the Vital Statistics Agency. They have offices in Victoria and Vancouver. You can also access copies through British Columbia Government Agents throughout the province. If you need information on official Government Agents, locations of Vital Statistics offices or mail-order instructions they are available online.

Manitoba

If you were born in Manitoba you need to include a copy of your "large" certificate. If you don’t have a copy you can obtain one from the Vital Statistics Agency. They have offices in Winnipeg (254 Portage Avenue, Winnipeg, 204-945-3701). If you need more information or mail-order instructions they are available online.

New Brunswick

If you were born in New Brunswick your immigration paperwork should include a copy of your "long-form certified copies" birth certificate. If you don’t have a copy you can obtain one from the Vital Statistics Office. Their office is located in Fredericton (435 King Street, Suite 203, tel: 506-453-2385). If you need more information or mail-order instructions they are available online.

Newfoundland and Labrador

If you were born in Newfoundland and Labrador you need to attach a copy of your "long-form certificates" birth certificate. If you don’t have a copy you can obtain one from the Vital Statistics Division. Their office is located in St. John’s (5 Mews Place, tel: 709-729-3308). You can also request a copy via one of the Government Service Center locations around the province. If you need more information, locations or mail-order instructions they are available online.

Northwest Territories

If you were born in Northwest Territories you need to make a copy of your "restricted photocopy" or “framing” birth certificate. If you don’t have a copy you can obtain one from the Registrar General of Vital Statistics. Their office is the Registrar General of Vital Statistics in the Inuvik Office of the Department of Health and Social Services ( tel: 867-777-7420). You can also request a copy via mail written to:Registrar General of Vital Statistics, Government of the NWT, Bag 9 (107 MacKenzie Road/IDC Building, second floor), Inuvik, NT, X0A 0T0 (fax: 867-777-3197).

Nova Scotia

If you were born in Nova Scotia your immigration paperwork should include a copy of your “large" birth certificate. If you don’t have a copy you can obtain one from the Vital Statistics Office. Their office is in Halifax (Joseph Howe Building, 1690 Hollis Street., ground floor, tel:902-424-4381). If you need more information or how to order via mail they are available online.

Nunavut

If you were born in Nunavut you need to attach a copy of your “large" birth certificate. If you don’t have a copy you can obtain a certified copy from the Vital Statistics Division. Their office is based out of the Kivalliq Regional Office of the Department of Health and Social Services (tel:867-645-2171). You can also request one via mail by writing to: Social Services, Bag 3 RSO Building, Rankin Inlet, NU, X0C 0G0 (fax: 867-645-2580).

- Note: Before April 1, 1999 Nunavut was part of the Northwest Territories. So if you were born in the Nunavut region of Northwest Territories before 1999, you should request your birth certificate from the Northwest Territories Registrar General of Vital Statistics.

Ontario

If you were born in Ontario you need to attach a copy of your "large" birth certificate. If you don’t have a copy you can obtain a certified one from the Office of the Registrar General. Their office is located in Toronto (Macdonald Block, 900 Bay Street, second floor, tel: 416-325-8305). You can also request a copy via one of the Ontario Land Registry Offices and Government Information Centers located throughout the province. If you need more information, locations or mail-order instructions they are available online.

Prince Edward Island

If you were born in Prince Edward Island and are completing your immigration paperwork you need to attach a copy of your "framing size" birth certificate. If you don’t have a copy you can obtain a certified copy from the Office of Vital Statistics. Their office is located in Montague (126 Douses Road, tel:902-838-0080). There is also an office in Charlottetown (16 Garfield Street, tel:902-368-6185). If you need more information, locations or mail-order instructions they are available online.

Quebec

If you were born in Quebec you should attach a copy of your "certified copies of an act" birth certificate. If you don’t have a copy you can obtain a certified copy from the Direction de l' Etat Civil. Their office is located in Montreal (2050, rue de Bleury, sixth floor, tel:514-864-3900). There is also an office in Quebec City (2535, boulevard Laurier, Ground Floor, Sainte-Foy, tel:418-643-3900; fax:418-646-3255). If you need more information, locations or mail-order instructions they are available online.

Saskatchewan

If you were born in Saskatchewan you should attach a certified copy of your "frame" birth certificate. If you don’t have a copy of this birth certificate you can request a copy of a registration from the Vital Statistics Office in Regina (1942 Hamilton Street, tel:306-787-3251).

Yukon Territory

If you were born in the Yukon Territory you should obtain a copy of your "large" birth certificate. If you don’t have one you can request certified copies of a registration from the Vital Statistics Agency in Whitehorse (204 Lambert Street, fourth floor, tel: 867-667-5207) or a Yukon Territorial Agent. Further information, including mail-order instructions, is available online.Hopefully this article has helped you understand exactly what Canadian documents you need to prepare and where you can find them when tackling immigration paperwork. Please share this article if you know someone from Canada that can use SimpleCitizen.

Perhaps it may be found within a different category.