Whether you plan to come to the United States for a short visit or a permanent stay, your first step is to apply for a visa.

Many people think they can show up at a U.S. embassy or border post, describe why they’d make a good addition to U.S. society, and be welcomed in. Unfortunately, this is the exact opposite of how the U.S. immigration system works.

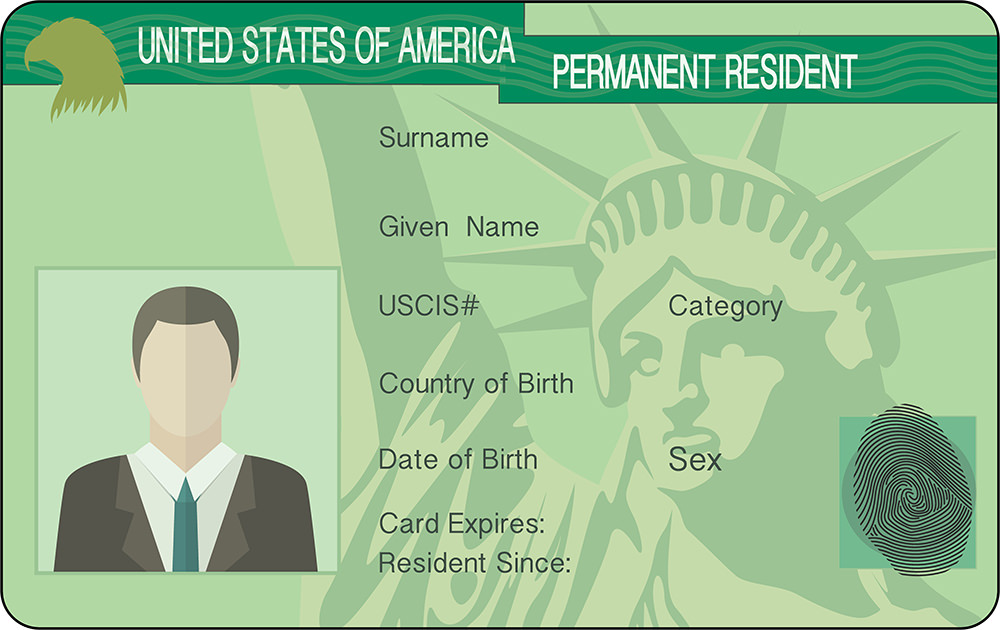

Instead, people who want to come to the U.S., whether temporarily or permanently, must determine whether they fit into eligibility categories for either “permanent residence” (a green card) or for a temporary stay (“nonimmigrant visa”).

Then they must submit an application — in fact, often a series of applications — to one or more of the U.S. agencies responsible for carrying out the immigration laws. These include U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), which has offices across the United States, and the U.S. Department of State (DOS), which manages consulates and embassies around the world.

What is a Permanent Residence? (Green Card)

If you want to be able to make your permanent home in the United States, you’ll need what is called “permanent residence,” or a “green card.” Green card holders can live and work in the U.S. and travel in and out, with very few restrictions (though they can’t vote, and can be deported if they abuse their status).

Family members of U.S. citizens make up the largest number of green cards issued each year. Others are issued to investors and workers who have been petitioned by U.S. employers or have special skills. Still other categories have a humanitarian basis, such as refugee or political asylum status (which can lead to a green card), for people who are fleeing persecution.

What is a Temporary (Nonimmigrant) Visa

People who want to come to the United States for a limited time need what is called a “nonimmigrant” visa. This lets them participate in specified activities (such as studying, visiting, or working) until their visa runs out. Students and businesspeople make up the largest groups of nonimmigrant visa holders. Nonimmigrant visas are also issued for tourists, exchange visitors, and workers with some kind of specialty that is lacking in the U.S. workforce. For more information, see

Exception: Visa Waiver Program

A visa is not necessary for short-term visitors from one of the Visa Waiver Program countries listed at http://travel.state.gov. You can come to the U.S. for up to 90 days for business or pleasure purposes if you’re from one of these countries. You will, however, need to present a machine-readable passport. Also, beware: The ease of your entry is balanced by the ease with which you can be kicked out — you automatically give up many rights and benefits when traveling without a visa.

To enter on a visa waiver, simply present yourself, your passport, and your ticket home to the officers you’ll meet upon arrival. If you come by land through Canada or Mexico, you’ll also be asked for proof of sufficient funds to pay for your stay.

Applying for Immigration Rights

After figuring out what type of visa or green card you’re eligible for, you’ll need to figure out how to get it. Most people (with the occasional exception of Mexicans and Canadians) must obtain a visa at a U.S. consulate before departing for the United States. If you’re already in the United States legally, you may be able to apply to “adjust” your status to permanent resident, or “change” your status to another type of visa.

Where to Find the U.S. Immigration Laws

Your possibilities for a visa or green card are set out under U.S. federal law. Being “federal,” the law is the same across the United States, unlike state laws, which can vary by state. If you want to read the U.S. immigration laws — which very few people actually want to do — they’re found in Title 8 of the U.S. Code, or in the Immigration and Nationality Act (I.N.A.) In addition, information on how USCIS intends to carry out these laws is found at Title 8 of the Code of Federal Regulations (C.F.R.). The DOS regulations are at Title 22 of the C.F.R. The CFR can be searched at the Government Printing Office website.

The trouble is that even lawyers have trouble researching the U.S. immigration laws — they’re considered to be the most convoluted and easily misunderstood portions of all U.S. law. But if you have a specific reference to a section that you’d like to read for yourself, by all means, look it up, then seek professional help if you need it.

Your best bet for getting any professional help with your immigration situation is to hire an experienced immigration lawyer. Ask friends or local nonprofits for referrals or go to the website of the American Immigration Lawyers Association (AILA).

Whatever you do, don’t go straight to USCIS for advice. The people who staff their front desk are not all well trained, and if they give you wrong information, they take no responsibility, even if it causes your deportation or destroys your chances of immigrating. This happens!

Many of these immigration laws are interpreted in U.S. Immigration Made Easy, by Attorney Ilona Bray (Nolo), including how to obtain many different visas, including the K-1 visa for fiancés, the B-1 and B-2 business and tourist visas, the H-1B, H-2B, and H-3 visas for temporary specialty or agricultural workers, the L-1 visa for intracompany transferees, the E-1 and E-2 visas for treaty traders and investors, the F-1 and M-1 visas for students, the J-1 visa for exchange visitors, or the O, P, or R visas for temporary workers, and how to get a green card through a family member, through the Diversity Visa Lottery, or as an asylee or refugee.

The Risks of Lying to the U.S. Government

One of the worst things you can do to your chances of getting a visa or green card is to lie, either on paper or during an interview with a U.S. border or other immigration inspector. Lies can have both immediate consequences, such as not being able to enter the U.S., and long-term consequences, such as not being able to get a green card — ever.

|

|

Who Can Be Kept Out

No matter what eligibility category you fall into — whether you’ve married a U.S. citizen, received a job offer, or been accepted to a school — the U.S. has the right to say no. And not just because there’s something wrong with your application. The immigration law contains a list of things, like crimes and certain diseases, that makes someone “inadmissible.” For more information, see When the U.S. Can Keep You Out.